Tuesday, November 14, 2006

Banana leaf musing

As my mom used to say, there's nothing more reassuring than watching someone enjoy their meal.

Monday, October 30, 2006

keep the change

It’s a fine line between a gift and a bribe. And a lot of people think no one sees that line anymore. When this man slipped a Rs.100 note to the driver “for tea”, and shone a servile grin at me, I wondered if it didn’t matter to him that the entire street was watching. All eyes hoping that his possibly representative offering will bring a Corporation official to dry their waterlogged homes. Maybe the press could pressurize the real authorities to act. Let’s flatter their ego, whoever they are, if they show a little worry about our stinky streets and open manholes.

The man actually managed a hurt look when we slapped his hand away. Immediately, he appealed to my cameraman. As if saying “You’re a man, you know the ways of the world. Let’s let little honest girls be righteous… come on, let us men be realistic.” And the street was still watching. Some soft confident grunts even insisted we stop making a fuss. Once threatened that he was risking us covering his locality at all, he put the dirty money away reluctantly. Not only was he still not convinced we were for real, he clearly thought we were idiots and wouldn’t survive in this bad bad world.

But I do think I won’t survive in this bad bad world too long. If you’re not screeching down the road, the traffic won’t part for you. If you’re not a foul-mouthed feudal lord, many who work under you do not respect you. If you’re not a hard-ass bribe-taking (and giving) reporter, you don’t get the scoop. Forget the scoop, you don’t even get what every reporter in the world and his never-leave-the-office editor has got. The realization makes me feel old. And pitifully young. At the same time.

Another day, a man in the court slipped a 500 to a tamil newspaper journalist. In a few minutes, he was powdering his precious nose for many camera interviews. “Should I look at camera or to my left? Is this white shirt a problem? Yes, yes, I’ll wear my robe” He’d done it all before, and parroted what some would consider quotable quotes. Nothing clever, nothing funny. Just TV-lingo that TAM and other organizations making money out of scientific ice-vecchufying (flattering) would pin-point as the words “Indian households tuned into”. Sure, how their hair must’ve stood on end when the powdered nose quivered in passion to “Justice must be done!” But his 500 mars his credibility.

Maybe they've learnt a hard lesson from the sharks of the journalism trade. Maybe they want to make sure they’ve done all they can. Leave no stones unturned, is what they say, I think. But the lady can demand to know when her story will come on air when I’ve just walked into her home and stuck a camera in her face. The uncompensated can expect reaction, even if temporary, from the authorities if they see the story. The ones fighting for their homes have every right to demand an answer from an often TRP-enslaved me when the twist of a cricketer’s knee elbows out their unfair eviction. But they cannot demand a space in the viewers' minds by handing me a note. Many journalists will continue to make the aggrieved believe in their supreme, far-reaching individual power. But if they’ve done so for a few sodden rupees, their power is not that supreme, is it?

Why is there widespread trust in underhandedness? Money makes the world go around, someone I didn’t much pay attention to, used to say. But if it’s your money, can it please just pass me by? I’d like to keep my conscience. They say it’s getting rare.

Wednesday, October 11, 2006

Sunday, October 08, 2006

baby you can drive my car

There is a remarkable amount of talk about women drivers. The usual accusations: too slow, can't park, too panicky.

It is believed that every woman driver, without exception, sucks. There are still some countries where insurance companies refuse to cover women drivers. There are books dedicated to the subject. Example: "28 Days: What your cycle reveals". We understand, the book says, you have menstrual cycle, you poor girl. It isn't your fault that PMS makes you take the wrong lane, it consoles. But also suggests that anyone with lower levels of oestrogen is bound to be a better driver.

There are tons of "humour" websites with photographs of bizarre accidents and cars stupidly parked inside pedestrian subways, and a caption in capital letters reading "Yes! It's a woman!!" Some driving schools in Chennai too offer women learners longer classes so they don't hit the road in a hurry. The nicer people empathize with this innate incapacity to drive: maybe she's born with confusion about gears.

Yes, bad women drivers do overtake from the inside, they do maintain irritatingly low speeds on highways, they do take ages to park. But the bad male drivers (yes, they do exist) do the same things without being bumped/rushed/yelled off the road for their road skills, or alleged lack of them.

An Australian Transport Safety Bureau's website makes an interesting observation from accident statistics involving men and women drivers. The national toll is decreasing, they say, but the number of women drivers killed and hospitalised is increasing. "This is due to an increase in the number of women obtaining drivers' licences and an increase in the amount of travel they are undertaking." If there are more women figuring in the accident statistics, it doesn't immediately mean they're getting worse by the minute. It just means more women drivers are now included in the total count.

Busy as we are shaking our heads ruing "these women drivers", we forgive those men who would take sharp swerves around wrong sides in peak hour traffic to say, "Madam, what are you doing?" Whatever we might say about women at the wheel, it is hardly an equal road for her and her male counterpart. The teenaged boy shifting gears lurchingly isn't offered a Traffic Rules manual at the next signal. The man on the cell phone driving in the two-wheeler lane doesn't get knocked on his bumper by angry motorists. When the call-taxi always in a hurry whizzes past a red light, no one yells expletives about the driver's flawed genes. And no male driver has to try and block out the lurid gaze of the woman in front, twisting her rear-view mirror for a better look at his chest.

Update: Some phew-ness here.

Friday, September 22, 2006

the world needs cartoons

This is fun! Let me see... Mine is: I eat a lot of rice, and come up with stunningly crackerjack last minute ideas."

Tentative name: Last minute rani (with a ticking clock showing 11th hour in the background)

What cartoon are you?

Sunday, September 10, 2006

BlogCamp!

I went, buzzed around, and because I was covering it, didn't get to listen to anything except for one little limerick by Aparna Ray. Were there really just 200 people at the BlogCamp? That was supposed to be the upper limit of the number of participants, because as Kiruba says, "After that, it's either too chaotic, or we'll have to induce structure to make things more orderly." And at this event, asking for order and structure is blasphemous.

What excited me was that in a BlogCamp, if you're in the audience, and can't believe how boring the speaker is, you can actually stand up and show him how wide you can yawn. Fun, but that's a long way off. The rules have been broken for you, but it takes a while to relish that freedom. While some people sat with legs crossed on the table, some others hissed "How rude!" on the side. Teachers in school have trained almost irreversibly to only speak when we're spoken to. You wanna say something? You raise your hand, buster.

But the unconference did show signs of weaning its participants away from the usual conference etiquette. I caught at least half the people bringing their lunch plate to the table; those who didn't have probably had bad (and common) experiences of sambar splashes on their keyboard (No, drumstick sambar was last week. This week T,H, and N have slurped onion sambar).

There were bloggers who talked about pet fish and pandas, fashion (unrelated to the pandas), rural connectivity, disaster management, sleeping on the job while your blog earns for you, body shopping, blog journalism, podcasting, firewall skirting, how to avenge those that steal your content, how to increase your hitcount (I need to learn a thing or two), how to be likeable.

But today, a certain sense of wooziness was perceptible as soon as I entered the room. When I asked if it was post-lunch ennui, someone corrected me. “Post Beach House party booziness!”

I wish I’d hung around a little longer, but as soon as too many people started noticing my CNN IBN mike logo and saying "Why don't you attend my talk on a very pathbreaking concept," I decided it was time to leave. After all, they know that a little appearance in the media can do much for your blog. At the same time, I did know of some interesting bloggers like Amit Agarwal only through TV. It’s not surprising that blog-branding and promotion was one of the talks. But I was primarily looking out for blogs with a cause, and found Osama Manzar. He doesn’t blog himself, but came from Delhi to ask bloggers to be responsible in their writing—in that they don’t just detail their breakfast menu, but write of what they see in their travels. “Not take Coca Cola to the villages, but bring the sherbet to the city,” he said. His Digital Empowerment Foundation searches for solutions to bridge the digital divide. They’re the guys that awarded the now quiet and bitter youth, Raghav Mahto, for his enterprise in running his own radio station from rural Bihar.

I expected less tolerance for clichés in such an environment, but politeness and a will to be democratic let some sessions unclocked. Of course, it’s also probably just my patience that needs work. But being at the BlogCamp (even for a few hours) was great— you can almost hear the whirring of minds. And it’s a place where you meet so many you’ve only just read before. Even for those who spend more time in the virtual world than in the real one, shaking the hand of your favourite URL can put you in a great mood.

Thursday, August 24, 2006

Jussst missed the elephants

I decide to have a Kodaikanal holiday that isn’t ditto my dad’s 25 years ago. Since then, I hear, too many honeymooners and rowdy boy gangs have taken over. But surely there must be more to Kodi than just a repetitive line of rocks giving different views of blinding white mist. Surely it isn’t already explored out.

If you’re desperate enough for something new in this old, old place (since 1845), look behind the rocks the guide’s pointing at; demand to turn left when he turns right; look at the little cottages hidden from view by the mammoth holiday home. It takes a gritty kind of tourist to outfox the local travel guide. But when you manage it, you’ll find a door into the Kodi that is only for special guests.

But first, promise you won’t stone the monkeys. Or etch your eternal love or turbulent lust for someone on a tree trunk.

All right now we’re ready.

On the winding drive from Kodaikanal Road Station to Kodi at around 5 a.m., I try not to make a list of things to do. A list means structure and itinerary, which means asking someone for directions, and that means going where everyone’s been and is still hanging around. Instead, I talk to the driver. “So many tourists spoiling your town, no?” By the end of the three-hour drive, I’m armed with ideas and a determination that will keep me away from anything that has an attached shopping street. Or a bellboy.

I drive to Cinnabar, literally my home for three days. The man of the house, Bala, has two rooms and his entire home (always filled with delicious smells) to offer. After Kodi’s first cold wind has frozen my nose, it’s a relief to walk into a room that’s warm, delightfully distant from the overcrowded Kodai Lake area, and only two steps away from the kitchen. Breakfast is wholesome, and reminds me of something that will definitely only happen at home. Being cajoled to eat more because it’s good for you. Bala inducts me into family. I’m to say hello to the canines sprawled on the grass: the three-legged handsome Hero, and the slightly cynical Cookie. Then I’m packed off with a bottle of water to go find my own Kodi.

If you look a little lost around Kodai Lake, you’ll have at least four people walking up to you chanting names of ‘points’, ‘sights’ and ‘treks’. I say I don’t want to see touristy places, only directions to a certain Guna Cave. Shock, awe, disappointment: It’s a place that’s fenced with barbwire ever since 12 boys decided to go too deep into the caves five years ago, and didn’t come back. The crowd disperses, except one man. Selvam is a driver-cum-guide, and once I’m in his Ambassador, he fishes out a little book of 28 must-see sights. Published in 1975.

Guna Caves is the local name for Devil’s Kitchen, a deep bat-infested chamber between three naturally arranged imposing boulders (Pillar Rocks), a sight that is listed in Selvam’s book. It’s now called Guna Caves after it was turned into a romantic kidnapper’s lair for a Tamil movie. Loud teenagers stand just outside the fencing around the cave, screaming angstful “Abiramiiiii!”s (name of kidnapped in said movie). Selvam and I go around the base of the pillar rock. Me, petrified about being the potential thirteenth ghost in the cave, and Selvam, looking for a certain hallucinogenic ‘magic mushroom’ that gets him a good price from “Keralites and foreigners”.

We find an entry, veiled by bramble. “It’s a path only some of us know about,” says Selvam. The rocks are loose and wobbly, the fluorescent green moss making everything slippery. Bats are shrieking from somewhere really south, and we, errr… are heading in the same direction. Someone is haggling for a kilo of carrots somewhere far above and it sounds warm and safe there. Inside Devil’s Kitchen, however, the air’s muggy, the walls smooth, with little shelves that look perfect for a perch. Selvam chucks a pebble that’s instantly swallowed by the darkness. We hear the plonk only after about 10 seconds, and a crash of wing flapping (of bats we jolted awake). We’d discovered fresh country by simply stumbling on it. This is the kind of place that teaches you to how important it is to have a firm footing.

It’s almost four p.m., and Selvam goes off for a trippy omlette garnished with chopped magic mushroom. I grab a muffin and glass of hot chocolate at Pastry Corner, where you can hobnob with the old and famous from Kodi. Prasanna and his sister have run this cosy little bakery for years, dishing out heavenly Chickoo icecream, pizza, and whatever else you see in the store.

The streets near Kodai Lake are unusually deserted. Either it’s naptime, or the punctual afternoon rain has driven everyone indoors. I find The Art Gallery that’s spot on for penniless idlers. A dramatic Lotus theme quilt hangs on one of the walls. Differently sized canvases fill the two small rooms. Adam Khan, Cristina, J. Nath, Richard Pike. Not very local sounding, but the creator of every piece of art in this gallery has a home in Kodi, and each work of art is a sketch of the everyday life of the town’s people.

Back at Cinnabar, Bala introduces me to more family—Vasu, the lady of house, and Vidya, their 17-year-old daughter. We sink into the sofas in the fireplace defrosted living room, and agree with lethargy-softened passion that city life is for slaves. Why doesn’t everyone move to the hills? Defiantly, we proceed to the Middle Eastern dinner, in which every single vegetable, exotic or not, is plucked from the garden. And dessert, an affable cheesecake, too is thanks to a cow milked in Bala’s farm, and cheese made in Cinnabar’s own kitchen. Seriously, it’s like a Ukrainian folk tale.

The next morning, after another solid breakfast, I’m packed off with a bottle of water again. Today’s Kodi is one of the fugitives; people who ran away from the belittling enormity of cities to lend their paintbrushes some colour. People who found a town that gave them enough room to breathe.

J. Nath is a sprightly Punjabi artist who gave up Bombay’s pace 25 years ago for Kodi’s unpaved roads and potato farms. The plot next to his, Senora Garden, is a failed attempt at tempting the city-weary into a cottage on the hills. It has to be done right, like J. Nath’s home. Full of daylight shining in through large glass windows, the ceiling low enough to touch. Brushes and palettes strewn about; canvases at different stages of completion. And two little cushioned chairs. One for the white-bearded storyteller (him) and one for the enamoured (me). Nath tells snaking stories of travel; getting lost in the characters memory throws up. Once in a while, his wife Jaya points out to him that it was in 1983, not 1982 that he lost his graphic printer job at Dubai, and Rs.340, not Rs. 350 was the price of the first painting he sold.

Nath doesn’t waste paint on anything sad. Nothing can make him paint a tear, or the violence of rage. “Why not just brighten our walls and our lives?” His pointillist style and vigorous colour scheme adorns every wall in the famous Carlton Hotel of Kodaikanal. For superb tales about old charming Kodi, changing Kodi, and masala tea, Nath is the man to meet. He won’t care if you don’t even look at his artwork, but you won’t be able to help it.

Just a few minutes away from Nath’s home is Bharat Bakery, the only place in Kodi for incredible ginger biscuits. I munch them on the way to the ‘quilt lady’— Jayshree. The architect of the Lotus motif quilt in The Art Gallery. In a house next to hers, five women work with needle and thread, carefully sewing each puppy, jungle scene, and butterfly into the intricately designed quilts. They came to Jayshree from broken homes, and now they’ve together built their lives around the income and warmth the quilts bring. Jayshree had learnt quilting in London, before she too came away for a quieter life. Many visiting Kodi step into Jayshree’s little factory to learn a little quilting, and to sew personality into an otherwise rug.

The rain’s back again, and so is my excuse to laze. The chai chat with Bala roams around the valleys of Kodi, and stops at Joey. This man’s address could say: A. Joey, No.1, Kodaikanal Shola forest. Joey’s grown up bathing in waterfalls, watching elephants saunter by watering holes, and panthers slumber in his farm. Before the rural road connectivity project half a decade ago, Joey trekked up 20 kms of hill to buy his month’s supply of rice. Today, he’s a family man with a Maruti Omni. And anyone’s welcome to his wild home.

Bala takes me to Joey’s early next morning. The 45-minute drive of anticipation ends in an unbelievable house right in the Uthamapalayam range. Joey waves at us, and immediately wants to show off his backyard: the jungle. Throughout the four-hour intense trek, not once does 51-year-old sit to rest, or glug down water like one of us half his age did. He instructs us to not lose it if we saw an elephant, and do exactly what he does. Scramble up a tree. “You can climb a tree, right?” he asks, and I’m not sure he’s joking.

“Look, rosewood tree”. “You have a wound? This herb is a coagulant”. “A bear’s been at this beehive”. “Smell this. Wild lemon”. Joey enjoys the forest and its details. Things we can only gape at, and try to cram for an article. A fat bison runs noisily across a stream and Joey’s after it in a second. “Come, come! Bison! See it!”

The elephant valley, however, is Joey’s forte. Trees they’ve rubbed up against, the age and contents of the dung, the herd’s mud bath locations. Niceties only love and a long relationship can teach.

When we return (several kilos lower, I’m sure) to his home, there’s a hunter-gatherer lunch. Papaya, beans, drumstick. “Oh, it was just growing in my backyard.”

I did what I set out to do after all. I found the Kodaikanal I wasn’t looking for.

For Outlook Traveller, September 2006.

Monday, August 07, 2006

Friday, August 04, 2006

Tuesday, July 18, 2006

Keep out because we've said so for ages

Saamis will soon be all over town, throwing away their cigarettes and slippers, sleeping in the living room, and turning on their goodness for 41 days.

"Swamiyeeeii! Sharanam Ayyapppa!" is a chant I've heard and enjoyed every year, as my father would wear his rudraksh necklace, and suddenly turn so pious that I felt respect and fear soar inside me. I liked that he suddenly sported a beard too; it made him handsome. His friends planned the trip for a whole month: cars to be booked ("We're getting older, the Tempo will give us slipdisc. Get a Scorpio"), leave to be applied for, and celibacy to be attained. It was a man's holiday from the household, but these men were truly believers. They loved their Ayyappa and didn't fail to bring home the cherished Aravana payasam (prasad) that we licked for weeks after. I'm glad I got to go once when I was nine, and while trekking up the hill, some uncle even took the bundle of divinity from my head and threw it on his. "Little girls needn't bother."

Looks like not-so-little girls needn't bother either.

"Jayamala shouldn't have entered the temple."

Why?

"Because she's a woman, and women are not allowed inside the Sabarimala Temple."

Why?

"Because Ayyappa is a bachelor and he doesn't like women entering his temple."

Did he tell you personally? Did he have a nice booming godly voice?

Jayamala didn't just touch Ayyappa's feet; she hurt male pride. How dare she enter what God said was man's space? To add to that, an unnecessary court directive a few years ago asks the temple authorities to enforce the ban on women strictly. Now that Jayamala said she entered the temple 19 years ago, suddenly so many men are afraid that the fellow they've been worshipping all this while is a dirty fellow. Touched by a woman. Did it mean that all that work they put into leading a pure life was a waste? "Ermm... so can I smoke again? God ain't that pious anyway."

Rahul Easwar, grandson of the chief priest of the Sabarimala temple, is "a believer in tradition, but a feminist." That's how he describes himself. He's a VJ, wears stylish unwashed jeans, and could give Dhoni a run for his hair. He also chants Sanskrit slokas, seems to be a yoga expert of some sort, and said on a news show that he's is a believer in Sati. Whether he's that much of a believer in tradition, or he just said it to seem consistent on TV, we will never know. But it is this kind of Saami that worries me. The one who seems modern in every way, except that he's not too progressive. The fellows who have no qualms about clinking vodka glasses with their girlfriends, but would "be practical" in getting her parents to cough up dowry (To soften them up for the intercaste marriage). The kind of guy who "allows" his wife to work.

My dad and his middle-aged friends going to Sabarimala wouldn't care if their wives hopped along. Their sons who go along aren't really sure about this, though. They're still walking the trapeze between being a modern chappie who condemns the purdah system, and an Indian boy who must not question his tradition and culture.

Thursday, July 13, 2006

How stupid can be thought funny

Nevermore. Because they went ahead and okayed one of the worst ads ever:

Chase skirts now. Soon you'll be washing them. Eeeyuck.

This writer's justifiably annoyed in her post, and calls it the "wtf ad". But it's the comments that are shocking. Take a look. And at this too.

Maybe the ad-men (or some strange women) were suffering from testosterone poisoning.

Tuesday, June 27, 2006

Dei Ambi, ketayo?

A rascal was recently heard plotting annihilation of the dreaded tam-bram cult and stop forever curd-rice warfare in social, economic and virtual circles. As he sat with his cronies (software engineers from Bristol, New Jersey, Toronto and Tidel Park) one night-shift, he revealed his plan.

"We are to hijack The Hindu paperboy in Mylapore tomorrow morning. The Hindu must not reach Iyer and Iyengar hands! If that doesn't ensure heart attacks to every single mama on Kutcheri street, at least it'll ensure constipation."

Thanks, Meera, for this. A fantastic sociological finding:

A survey has revealed that 'Ambi Mama' is the leading relative among Tamil Brahmin families worldwide, with six in ten families having one of their own (a 60% repsesentation. Apparently, Ambi Mama held off stiff competition from Mani Mama (with 55% representation) and Baby Chitti (39%) for a well-deserved win.

"It's a great day for all Ambi Mamas. All the years of hard work-- drinking coffee, criticizing the Indian team selection and complaining about blood-pressure-- have finally paid off. Yay!", said Ambi Mama, a spokesman for the Ambi Mamas Association of Dear Old Rascals (AMBASSADOR), a division of the Hardcore Brahmin Organisation (HBO).

Yes, Vaidhi periappa did say, "Naangal ippo llaam broad-minded aakum." (These days we are all broad-minded). But...

Not all are happy with progress, however. "These youngsters are ruining everything by naming their children Archish, Dhruv and Plaha.", thundered Badri Athimber. "Can you imagine how it will sound? Dhruv Mama, Anamika Athai, Archish Chittappa-- Ugh! Phooey! That is so not cool!!", he growled, using expressions of disgust picked up from his states-based co-brother.

When asked for their response, several Brahmins living in Adyar merely arched their eyebrows, pursed their lips, and continued waiting for the December music season.

Update: Further research of the same. I think it's the vibhoothi overdose that's at fault.

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

the incident called monsoon

Next time, blog, I promise I will write exclusively for you.

---------------------

Rain is a big event only for those who don't see much of it. Those who see it in plenty scoff at any wide-eyedness about full rivers and rumbling clouds. People in Gokarna talk of a thunderstorm as if it were a tiresome old aunt who coughs too loud when everyone's asleep. For them, monsoon's just a time to wash clothes in smaller batches and make the umbrella the arm-extension of the season. A time when conversations with tourists go beyond giving them directions to the beach.

The conversations begin at Mangalore, where I take the local bus: the only sensible way to get to Gokarna, apparently. If you ask for a taxi (as I did), there will be no mistaking the utter disbelief on the driver's face. "Why spend so much money? Take the government bus." There is just one direct bus to the town, and if you miss that (as I did), then just let the wind and state transport take its winding course. The view from the shut window pane lashed with rain is worth the detours and retours. Don't let all the localites nodding off in the bus trick you into believing there's nothing to see on the way. They seriously have no clue they're living in a world of watercolour.

When I get to Gokarna, I ask for Swaswara, where I'll stay. It's just a month old, so the local name for this beach resort is simply, "aa hosa jaaga" (that new place). An autorickshaw man volunteers; his vehicle has curtains, big stereos, and a detachable door to keep out the rain. But no meter. I postpone the annoyance of having to haggle, and decide to enjoy the ride. As the autorickshaw the leaves the main town behind, it's as if someone switched off all the ambience. Except for the auto's putt-putt, and an occasional rumble from the skies that seems to shush any chitchat.

After a lot of quiet travelling, the road abruptly climbs onto the rain cloud we've been following. As the autorickshaw man switches off the engine and lets momentum play driver, I let my jaw drop. I can't believe I've seen white froth recede from sand. "Kudla beach, to your right," I'm told. Walled in by towering umber rocks that seem to relish every tourist's shock at suddenly discovering waves crashing underneath them. "There are three more beaches like this. Your hotel is on the next one," he points left, "Om beach."

When we're there, the autorickshaw driver seems almost shy to ask for money (though when he does, he's talking dollar conversion). He insists I figure out what he deserves, but manages a look of deep hurt and resignation when I give him what I think is a generous amount. "Foreigners never argue," he says. Guiltily, I slip him some more money, not realizing that I have now established a non-negotiable fee that he will forever hold me by. Still, I store his mobile number as "Only transport", and walk into Swaswara.

Their website had asked me to "be watchful, for here, spaces expand and time slows down." They've taken their warning seriously. My "room" door opens to a miniature Konkan villa, complete with cool red-oxide floors and tiled roofs. And, of course, the open-roofed bathrooms: initially unsettling, but gradually inviting more and more indulgent baths. The yoga room upstairs soon became my regular spot for tea and staring.

Five minutes from here is Om Beach, whose sands are footprint-free. Not because the sea does an impeccable clean-up job, but because monsoon is a time Gokarna goes from being a tourist spot to a town going about its business. People live on off-season mode, believing that tourists don't want their hair and feet wet. So although Gokarna's an almost round-the-year destination, most places that let out beach-shacks and cottages close down almost as soon as the first dark cloud makes its appearance. But those that are open are glad to have you, and serve up well-meaning chai and fried rice.

Even when Gokarna is introvert, it manages to make the endless expanse of the Arabian Sea seem like my own little holiday space; like all I have to do is clamber up another bump in the Western Ghats to conquer another bit of sea. From Om Beach, I walk a marked route up a mountain, stopping once in a while to get a top-view of the beach's Om shape. I stomp through a forest clearing for 15 minutes, simply following the sound of the waves.

Kudla Beach shines many shades of orange through the forest darkening after sunset. Palm trees line the beach, as if it's perfectly normal to stand there right next to big masses of sea-eroded boulders. A few fishermen venture out with torches, searching for fish that might get thrown up when the waves mess about in mountain crevices. When I'm done being stunned, I notice a board that says "Dangerous route. Do not use before sunrise or after sunset. Beware of robbers and thieves. -- Gokarna Police". A fisherwoman offers to let me stay in their house for the night, but I risk the walk (ok, ok, petrified dash) back to Swaswara. Thank you, good diligent man, whoever you are, for painting a white arrow every five steps up to Om Beach.

At Swaswara, I prescribe myself a Bollywood style shower dance in the open-roofed bath. At dinner, I look at the fish on my plate. Don't I know this fellow? "Just caught from Kudla Beach by local fishermen, madam," says Manjunath, 24-year-old proud wearer of F&B manager badge. There are vegetables too, in case it hurts to eat someone you've just met. The menu is flexible, and you'll get almost whatever you want. Even conversation. The staff will you tell you unbelievable season-time stories. Of when beaches are full of foreign tourists and backpackers from Goa who stay so long they have tabs in the town market. Of Gokarna (cow's ear) being named for the ear-shaped confluence of two rivers. Of how the man who runs 'The Spanish place' in Kudla fell in love with a Spanish traveller.

I sleep well, until it gets slightly colder and some fat clouds explode on top of the place. It rains with a vengeance here. Unbroken, noisy sheets of water. Till sunrise. Then the sky tells you to go on with your holiday. So I do. An auto takes me to town at the earlier standardised rate.

Gokarna is a little town, too high up in the Western Ghats to be bustling. October to February is the time most tourists land there, so a rare monsoon traveller is a delight, and is quickly assumed a pilgrim. Shopkeepers, temple priests, local tribes selling flowers... everyone is ready to break into a story. The temple town of Gokarna has about 18 temples i.e. more than two temples per street. When the shrines tend to get quite repetitive, someone suggests visiting only the town's main lord: Mahabaleshwar. It's the one temple stop to holiness.

There, a board says "Foreigners are prohibited inside the temple". A tad unfriendly for this century, what? Many agitated priests justify that god doesn't like unbathed people and they're not sure if foreigners bathe. Those they think are tidy are advised to spend a bomb for a Shiva linga puja. After a total flop of embarrassed bargaining, I try to get my money's worth by getting the priests to explain all the legends of the temple town. With illustrations.

Only a little wiser, I walk to the nearby Gokarna beach, the only one accessible inside the town. If it wasn't monsoon, and I wasn't a woman, priests would've persuaded me to appease my departed ancestors. A puja for the dead (tharpanam) performed at the seacoast is one of the reasons Gokarna's a sacred destination. But it's raining, and all I see is some snoozing Brahmins and white cows chewing on the discarded puja flowers.

The town covered in half a day, I head to the two beaches I've been warned to only touch by road: the Half moon and Paradise beaches, which can be reached by auto or trek. The adventurous spirit wins, and takes the forbidden path. This time, there are no white arrows to show the way. Just an often-taken muddy track that's now running off the cliff because of the non-stop drizzle. Some dependable rocks are held on to, and the photographer Kedar and I look down at the Half Moon beach. More peril, less sand, this beach. But any peril will seem worth it if dolphins suddenly slice through the sea surface. Four of them, like synchronised swimmers. We watch and breathe the sight in. The drizzle slowly turns impolite, urging us to turn back. Paradise is far, far, away and may be conquered in a safer summer.

The sand is shrugged and shaken off and one hand grabs the chai, while the other snatches the buttered toast. We await twilight for Kedar's "perfect blue sky". Whoever said rain would play spoilsport doesn't know how fair it plays the game in Gokarna.

Monday, June 05, 2006

Aei auto!

Automen are perhaps the most worldly-wise swindlers I've ever known. And in Chennai, all they have to do is narrate a few anecdotes and put forth a few cute theories that relate the water scarcity to Rajnikanth having been a conductor in Karnataka. And there you have the passenger just handing over his/her wallet to the sideways sitting man.

All for a hilarious, frequently disagreeable lecture about tamil kalacharam (culture) and splendid profanities yelled at idiot motorists... all for a show of personality and wit, I part with my not-so-hard-earned money. I throw away precious negotiating power the moment I giggle at 'yamma di, thodaiya yenna grip-la pudichirukka!' (wow, what a grip she's got on his thigh. Pointing at a girl and boy on a bike).

The carefully constructed scowl is all but menacing when my eyes shine interest in his speech about the irrelevance of arguing the banes of populism when the promised free rice is actually wanted, and being distributed. How to not give an extra 10 bucks to someone who's so angry about the thiruttu VCD (pirated VCD) crackdown; and so excited about seeing Pudupettai at Rs. 2 per head at home than Rs. 35 at the theatre. I pass the buck. If only to continue the conversation without interruptions about the ornament that is the auto meter.

Automen, they rule, but autorickshaws, they joggle bone joints. It's a strange relationship we have with autorickshaws. A strange flavour of love. Made of need, cheating, and entertainment. And when you think you can second guess all of their moves, you encounter this: The Indian Autorickshaw Challenge, 'the birth of a new motorsport'. A 1000 km rally through Tamil Nadu in a three wheel motorized vehicle. On August 21-28, 2006.

And if anybody has read the magazine Autokaran, then please do let me know where I can get hold of a copy.

Saturday, June 03, 2006

whose hand

READ HOLY THIRUKURAL

Seen on 6th day:

READ HOLY THIRUKURAL

THEN READ DAVINCI CODE

Thursday, April 27, 2006

Dammit they don't use flags anymore

It's the first thing I get wrong. Looking for one man. The board does say The Station Master, but that must've been nine platforms, 221 trains, and a century ago. These days, The Station Master at the bustling Chennai Central is actually a team of white uniformed, slightly rounded, intensely dutiful men. Three men, as one force, making sure we have enough time to cry our goodbyes, to give strict instructions about the milk in the fridge, to make a dash for a last minute bottle of water even as terrified moms snap at us to "GET BACK in the train".

The second bit of idiocy has something to do with the blazing warning the Railway higher-ups reserve for those eager to meet the railway staff. I'm scolded stiffly that my request to just observe the men at work will create a definite situation of imminent danger. Did I really want to be responsible for the sacking of the stationmaster, and worse, the deaths of a train full of people?! Did I not care at all for an inconvenience (me) free environment?

After signing something of a mea culpa, I set off grimly to the stationmasters' office. Karunakara Reddy nods me in, while Rajasekaran tries to look concerned about some article on rice politics in Tamil Nadu. Reddy is pleased that there are still people who want to "study" the work of stationmasters. "There are ladies like you in our trade, you know. But after one month as stationmas… err, mistress, they don't want to do standing work. They ask for a transfer and go sit in the office." This topic interests Rajasekaran and he speaks as if reading from the newspaper: "Sometimes I don't know what to think of woman power." Reddy laughs and elaborates the tiffs his friend has with his ambitious daughter. "Rajasekar has one plus, one minus, you see. One son, one daughter. Both want to work. My friend wants his daughter to be a housewife. He is an old fashioned man, you see. My wife, she is employed."

There is love light in his eyes, but without a word of consultation Reddy and Rajasekaran suddenly get up in unison and leave the room. The digital clock on the wall has blinked the call of duty. Train departure at 9 o'clock. On the way to Platform 6, voices in Hindi, German, English, and barely-there Tamil plead train numbers coaches, and ticket rates. Reddy has an answer for everyone, an encouraging nod nudging them ahead, partly so they find their way, and partly so they get out of his. "I know railway related lines in eight languages!"

Rajasekaran gets into a heated argument with the Freight Loading In-charge. "See the spring under the coach! It's jammed! The train cannot carry this much weight! Why don't you listen?!" His fists thump the side of the crates violently. Just then a confused family stumbles to him asking in Hindi for Coromandel Express. He's suddenly a soft mass of goodness. "This only, sir, this is your train. Get into the unreserved bogie. Be careful with your little girl." Beads of sweat escape from his nose tip onto a train of wetness on the front of his white shirt.

Reddy has meanwhile sorted the overloading issue with special negotiations. He points to the confused family and little girl getting on an already overflowing coach. "72 people in one coach are allowed. But see these faces peeping out." Faces peep out.

"Must be 150 per bogie. Mostly in northward bound trains." Rajasekaran joins in. His theory is that it's the north Indians who make travelling such a nightmare. "They carry trunks! Even ten-inched kids carry trunks!" He has a thing or two to say about the "arrogant army fellows" too and where he'd like them to shove their trunks.

A reverent worker from the Pantry Car informs Rajasekaran that there's no water on board. Five minutes later, private supply has been arranged. Is that ok in a government-run monopoly, I ask, obviously a fool to have. "Solutions. Quick solutions and good water. That's what people want," Rajasekaran says. Apparently, people bear the toilet stink and sometimes acrid train food because deep in their heart they know "no other country will allow hanging from a train like this." "Passenger oriented railways… new meaning, no?" laughs Reddy.

Somewhere along the 155 years of Southern Railways, the stationmaster has become an oracle, a voice of good sense. A voice with an answer to any existential dilemma in all that mad chugging of wheels. Reddy and Rajasekaran agree that to the passenger, they're the front office guys. Probably thanks to the Southern Railway mascot, an exceedingly friendly looking elephant with blue tie and a trunk-held lamp. Rajasekaran chuckles about how he is the living mascot sans the friendly face. "I keep a scowling face when I'm bored of answering stupid questions."

But the real responsibility takes more than a friendly face.

And that's where Balasubramaniam, the third man, (no, he wasn't forgotten) comes in. Not friendly, not ready to answer questions, not wearing his uniform. "Who's going to see?" Far away from the passengers, his world is up in the second floor Cabin, amidst the buttons and knobs and brakes. And the constant ringing of the eight phones. At one point, he was "calling driver of Jaipur train" on the microphone, with three phones tucked under his jaw, filling in complicated numbers of arrival and departure in a record. The driver of Jaipur train was not responding. And the train was rolling towards a platform that already had an engine stalled. But Balasubramaniam was still on the phone. "Even if he wants to bang the train into another train, my braking machine won't let it happen," he says, proudly turning a knob and smiling for the first time, "Of course, if upstairs authority says to crash Jaipur train into Howrah train, then it can happen." Whoa. Railway higher-ups? "No, no, God."

As he sits among his phones and knobs, Reddy and Rajasekaran, at work near the Guard's coach, find out that a split in a weak rail-line last month has got only Reddy blackmarked. Rajasekaran says guiltily that he has been let off because of his familiarity with the top boss. They both smile sadly at each other.

They're a team that has been together for over 25 years. Seeing trains grow longer, bogies getting fuller, and private advertisements in the station get louder. And as their senior officials go to collect their awards in the Railway Week celebration, the Station Master, all three of them, turn back to mark the arrival of the next train. 'On time'.Wednesday, April 12, 2006

the old man and the prizes he gave me

I first saw him as Purandaradasa, his earnest voice pleading with the Vittala shrine to give him one glimpse, asking if an untouchable's devotion was only worthy of rebuke. As B&W temple bells clanged and crashed into each other, I remember my dad imitating the nasal tone of Rajkumar's voice. Trying to flare up his nostrils like Rajkumar's would when he sang.

Then I saw him as the detective whose 'idea face' was a nose-flare and big wide eyes. Also imitated by appa even in front of guests. Then Rajkumar was a policeman, a father, a man to take behind the bushes and kissing flowers, a devoted son, a farmer, a smart smuggler, a special common man. But Purandaradasa with his pleading voice remained with me as the lasting image.

To my family, Rajkumar was the voice of devarnamas (kannada devational songs). None of this was about faith, or devotion, of course. In Bangalore, Rajkumars devarnamas always won first prize at any music competition. Buy that new tape. Write down those difficult lyrics. Get meanings from kannada miss at school… because you had to emote right to win the Kannada book on Tipu sultan. Or else you'd end up with second prize. A book on someone who didn't even have a TV serial to his name. When one Rajyotsava Day, Rajkumar handed the first prize certificate to me in Town Hall, and ruffled my hair, I told the whole school.

Every morning, Rajkumar played out of my grandmother's old radio. "How many times will they play Bhagyada Laxmi Baaramma?!" We'd knot our ties and polish our black shoes wondering aloud why so many of Rajkumar's songs had the word preetse and bangaara. Then after Radio City happened, Suresh Venkat brought us at least two Rajkumar songs per evening on the Kannada-only show. After Rajkumar was kidnapped, every day we'd go to college (very near Rajkumar’s Bangalore home), only to be packed off home in the afternoon because of possible rioting. We hoped everyday that he was well and healthy in the forest. Believing that his wellness meant our safety in our mostly-Tamilian neighbourhood.

When he was returned from the forest, we listened to Huttidare Kannada nadalli huttabeku being played over and over on TV and radio, with as much elation as the people we were afraid will land their lathis on our head. We'd forgotten how much we loved the old man, how much we had internalized him. As he became just something we grew up with, we had forgotten his ability to sway opinions. His proud refusal to use his stardom to step out of the studios into the assembly. His shockingly steady voice even at 60.

Still, he'd stopped short of being a legend in my home. There were too many 'legends' sitting in our living room: MGR, thanks to appa. Prem Nazir, thanks to amma. And Rajkumar, thanks to the land we lived and loved.

Today, the last of them has had his funeral swamped with love and tears. So many adjectives, so many anecdotes, so many garlands. Suddenly, my family's love for the man seemed a mere fondness.

Till appa messaged me: "Dr Rajkumar dead. What to do now?"

Monday, April 10, 2006

million times beating my heart

Rajkumar has acquired renewed fame, of late, in webspace because of this deadly video.

(the quality is not as bad as it is in the above pic)

I don't know how I had a merry childhood without chancing upon this.

A must for instant nostalgia, giggles, inexplicable bellbottoms (that too white) and aching need to suddenly be shaking your thing at an eighties villain's den.

Here, actual lyrics of the song:

if you come today, it's too early..

if you come tomaarow, it's too laite..

you pick the taaaime

tick tick tick tick tick tick (with super feet shuffle without tripping on white bellbottoms)

a-tick tick tick tick tick tick

a-tick tick tick tick tick

a-tick tick tick tick tick tick tick

daurrrrrrllliiing!!

Thanks to a certain phone-singer. And other amused bloggers in blogosphere.

I'll go now, because the taaaaiiiiime is too late! tick tick tick tick tick tick... a-tick tick tick tick..

Saturday, April 01, 2006

the tug

Thursday, March 30, 2006

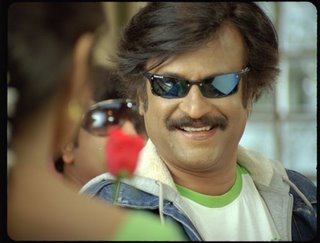

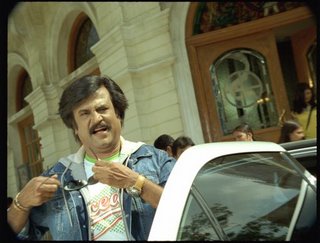

hair weave, superstar, things that amuse

What a style, i say! I still remember Chandramukhi's hilarious "Idhu yen sattai, yen dabbu, my kaas, my money! Naan kizhucchu poduven, thiruppi poduven!" Or something to that effect. Okok. It means "It's my shirt, my money. I'll tear it and wear it, or turn it inside-out and wear it!"

Vivek follows Rajni. I must take long dupatta to wipe my tears of laughter.

Well, isn't she shocked. Whatever for. It isn't as if they wouldn't have told her he's coming in cargos. Actually, i liked it better when he came in the white pant, and white shoes, in a bullock cart. Wonder what this character travels in.

Paarvaya paren... How sweet, the bouncy hair even has a shadow. :)

Whistlewhistle CLAPCLAAAAAP!!!!

Friday, March 17, 2006

whose festival?

It's difficult to explain to why, suddenly, blue is so offensive, pink so loud-mouthed, yellow so coarse, and green... cool green, suddenly so shrill, so vulgar. When they come charging like that, without a second thought about whether I want a stranger to slap me with colour or not, how can colour be just that?

It's simple. I have never played Holi. They all shopped for white, I went along. They sat for hours discussing whose house we could play holi in, whose parents will "allow boys". I hugged a cushion and sat in. They fixed the time. I said I was free. But then on holi, I'd have fever. Or my "strict parents didn't give permission". After a while they caught on, and it became another thing that was me. Friends understand. They don’t drag me out of the vegetable shop and say "Aaj holi hai, rang tho daalna hi hoga". And then crazy me with all that disgusting colour.

Whose hand is this? Why is it on my clothes? In my clothes? Why must I like your festival? You're not my friend. This is not my celebration.

Every channel kept saying, "If you’re an Indian, you will love the pichkaari, you will like the shower of colour." All day. Even after one guy in every office shouted himself hoarse about it only being celebrated in "most of North India". He was labelled intolerant and parochial. He’s only just protecting his personal space. Why must the stationary shopkeeper in Bangalore be the one to first tell himself to learn Hindi? It's telling that the first thing new-comers to Karnataka learn is "Kannada gotthilla", and in Chennai, it's "Tamil theriyadhu". Well delivered with the appropriately dismissive wave. That way, there is no danger of them accidentally learning a few functional lines in the language. Oh the horror.

I'd join in the festivities if I'd like. But I don't fancy eggshells sliding down my hair and unknown nails scratching my arm. But I don't like being told I must celebrate because Punjab and Delhi is. Chennai and Bangalore don't celebrate Holi. Some north Indians in these cities do. Why must their celebration be shown big on TV if no one cared about people celebrating Pongal or Sankranti in Haryana? I've had the pulls and pushes of a Delhi-centric 'national' English news channel lectured to me by many a long-timer. But it still refuses to permeate my brain. I still am offended that news from the South must fall in a separate show, too strange to naturally flow into other national news. Except, of course, when "South Indian film actor Mohanlal" acts in a Bollywood movie or when "Kannads ask for ban on non-Kannad films in theatres".

But let that be. Anyone who can't take anymore can run away from it all one day, can switch off the television. But what about the group of guys who accost the already-cowering girl on the street. 'If you don't want to play, stay indoors'. Even the police will tell you you should've stayed at home for your own safety. Just like you must stop going by train if too many people grab your ass. It's my freedom. It's your fault you’re such a spoilsport. Your fault you don't like being part of the games and feeling up. Aaj tho holi hai. Rang tho daalna hi hoga.

Wednesday, March 15, 2006

Thursday, March 09, 2006

counting sheep

So many thought-images just float by as my floppy pillow grows on either side of my head. It's like I'm burying my head in a cottony thought cloud. Sleep is far far away, because the horrible temple festival drum is beating nearer and nearer. (Do they really have to do it everyday? And isn't 2 a.m supposed to be the hour of demons?)

My flatmate, also awake, messages me from her room. "What do we have at home for homicide?"

*

Homicide. How easily, no? Amma felt sad about Rang De Basanti… nice jokes, she said. But "why did they show youth like that? I can't ever imagine that you'll have a bomb in your hand..." Was it depressing, ma? No, they're telling you there's no point. You're going to have to die for anything to change.

*

This lawyer and combed-over journo are talking. What am I doing standing here? I finished asking my questions, no? I pretend someone's calling me in the distance. I look away. For two seconds. I turn back around to see the lawyer's shifty eyes and his hand slipping into his pocket. The journo is nodding a thanks with a sick smirk. How much did he give him? Should I? Oh my wallet's in the car. Ways of the world, my dad used to say. You're young, you won't understand.

*

“You're too young to say 'I'm too busy to eat well'." The good doctor's office. Dettol smelling old nurse nods a "wait", walks away. The older nurse sits on the stairs leading nowhere. Grunts. Adjusts her thick spectacles. Dettol nurse wheezes and sits at the reception (Triple-god photo with... linear light, is it called?). "Where is that Jyoti? It's 8! Never does shift properly."

Old nurse: Why don't you leave?

Dettol: Young thing no... just married... night time, where she'll come?

Old: Didn't she have full morning? Leave it. Youngsters have no discipline.

Dettol: I had when I was in daawani (half-sari). No one to slap her into good behaviour, that's what.

Old: But that other girl Deepa comes correctly, pa! Didn't marry. Like us only.

Dettol: She will become a very good nurse.

*

"Aiyo I don't want one drunk fellow to hit me every night. My salary is for me only." But today she said, "I'm paying my brother's tuition fees that's why I work for you, ok?" Door slams. Usha akka. She laughs at us inside, I know. And shouts at me when I run for my crap leaving the milk on the stove. She doesn't like that I'm older than her by two years.

*

What a college thing to say. "Nothing goes with burger and fries like Coke". These children. But they get so tall these days. Maybe I should give up rice and take up buns and fried potatoes.

*

Potatoes are stinking in the kitchen. Only till the end of the month. I have to leave.

*

Oh, Saturday is my off. Will meet...

Ah. Sleep.

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

an urge to spit fire

Having a hate and love is not just difficult, it's supposed to be wrong. Look at the greys, they tell you, use your mind. Yes, the mind does tell me that I can't do anything about 99 people refusing to simply say the truth about what they saw. But it makes me nervous about justice, about what'll happen if my sister is shot in the head for refusing someone a drink. Ok, not "nervous". I'll say it. I'm shifty-eyed, breathless, cold, restless, scratching-thin-white-paper-with-a-sharp-pen petrified. My mind has been seeing flashes of thousands of faceless people standing thirsty, crying, bawling, their eyes bloodred screaming where do I go now, who will make me feel better, why did I ever hope, I should've killed him when I could.

And when a father says he wants his son killed because he can't afford to do blood transfusions for him anymore, I want to slow the world down and make it see. He's calling out for help, don't you see? He'd gone everywhere for help. Where were all you NGOs, MNCs, kind-eyed tearfaced doctors till now, till the media came and threw his misery in your face with slow, sad music and interviews of the boy himself saying "yes, I'm sad to die" (did they ask him how he felt about dying?!). Dr. Rajkumar, who "adopted" the boy, hid him and the father in his Lifeline hospital, bringing him out only to tonsure his head sympathetically on Jaya TV. And channels shout at their reporters for saying clearly in their story that the doctor only wanted to hit headlines, and that he didn't even know what the boy had. Oooh, how can you defile the benefactor?

Of course, I'm relieved the boy gets help, even if it's from a media hungry doc who thinks nothing of performing some 50 hernia surgeries on poor people in 13 or so hours. Someone in my head is telling me to just shut up and let the boy get something. But if goodness is all that matters, why're are the other benefactors so enraged that the doc got there first?

I'm tired. I don't even know who I'm angry with anymore.

Wednesday, January 25, 2006

By the horn

It's surprising how easily my eyes get used to flying dust. How soon I forget the unsteadiness of the wobbly wooden gallery (goda) that is supposed to keep me 'safe' 30 odd feet up in the air. How stupidly I actually think I can leave half way through this.

The first thing I'm told at Alanganallur is that once I'm there for the jallikattu, there's no leaving. I look in horror at a chap sharpening his bull's horn with obvious relish. Seeing my face, Hari (local reporter who can find his way out of vast fields and bridges suddenly breaking halfway on rivers) reassures me that all the exit restrictions are so a clueless stroller doesn't get in the way of a bull running wild in the village. "There are no rules in this game, you see. The bull can be anywhere, and it can think anyone is the bull-tamer."

So that's what it is about: A thousand mad bulls; more than 10000 people packed in the backyard of a small village temple; and no rules. One by one, the bulls are let loose into an arena full of unarmed bullfighters who go right for the horn.

The lady-with-the-stick who let us on the third floor of her goda says it used to be a one-man-to-one-bull game. Even now, the loudspeaker announcer keeps yelling that only one man can tame each animal, and the others are to please peel off the bull and let it go. The crackly voice keeps saying, in earsplitting volume, that the prize (could be anything: pressure cooker, non-stick pan, pot, pan, ladle, goat, hen, cot, almirah, dish antenna (really), TV, steel plates) is only for the guy who hangs on to the hump for 50 metres in the crowd as the bull bucks and twists to throw him off.

But no one's listening.

In all that boozed blind bravery, the bulls don't have it easy. Their tails are bitten, eyes poked, their stomachs prodded with sticks. But after watching for a while, I realize that the bulls are the ones that are managing tons better than the hundreds that lie in the hospital for weeks after this day.

I've heard of dark tourism, but can't put my finger on what it is about jallikattu that locks people into a spell... I caught myself watching wide-eyed, my hand in my mouth, my feet ice-cold. I found myself pointing frantically to whoever was nearby. Look, just look at that bleeding man. We talk of numbers immediately... how many injured last year, this year, today. How many already dying of blood loss. Then another bull comes charging into the crowd, and my hand goes to my mouth again. Our behaviour is only short of cheering.

A toothless old man with a thigh full of proud scars tells me it all started when small pox affected Alanganallur (Madurai district) ages ago. People prayed for a cure, and decided on this "blood sacrifice". So if even a year goes by without a drop of blood smearing the village earth, he says the local goddess will make sure an epidemic hits the village. "Of course, these days, there's no small pox," he adds, "So maybe cholera will come."

They can believe anything they want, and have any sort of game. But what happens on the back of the arena can't be called belief. Pouring arrack down the bull's throat, stuffing gaanja in their fodder, tying heavy stones to their balls... These bulls are trained all their lives for jallikattu, kept in isolation in a dark shed, seeing just the tender. Then once a year, it is let out into a ground full of mad men clawing at it. The animal loses it in a second. A wild game is one thing, but do they really have to mete out planned torture?

Hari tells me it's all in the business of bull trading. If a bull is tamed, it's sold cheap. If it escapes untamed, it goes for a super price. But the highest bidding is for bulls that steal the show (I'm told usually Trichy bulls)... ones that give the audience something to watch... some poking, butting, stamping, bleeding.

When I feel sick about a man getting gored, I am angry at the freakin bull because it isn't as defenseless as the men. The next moment, I see 20 guys poking the bull, pulling at its legs, and sticking needles up its hooves. I'm immediately on the animal's side. Till it waves its horns at a man in its way, and his white shirt is suddenly soaked red. On, and on, my mind played games.

For the audience, that's probably what jallikattu is. A 24-hour test of conscience.

Saturday, January 07, 2006

Hello, hello, mike testing...

Voices rage, chests thrust out, and fists pump the air. Worries usually coughed into a coal-stove spill forth in a rush as soon as the husband leaves the room. "No, he won't know when the programme airs on TV. Listen, I'll tell before he comes back for lunch."

Babies, of course, without exception, land their toothless mouths on the mike, and claw at it with their little fingers.

White khadi shirts comb their sparse hair all to one side in an attempt to hide the bald patch, straighten their collars and backs, and clear their throat. They know what they are going to say, and have said it many times before. People have yawned in their faces, and their run-of-the-mill lines have never been used in TV stories, but they're on auto-motor-mouth. But try to ignore the guy, and he'll fetch the whole community to scream in sync about how the media is biased. "You upper class convent educated media only want to show the flooded houses of the rich guys. You don’t even care if a poor man's corpse floats by you. Let's see you trying to come back to this area! I'll break your legs!"

That it is dramatic and baseless is beside the point. But how to get out the situation? Stick the mike in his face. Scream, if you will, into the mike, I say. He won't say much, but will be happy, and his party cadres will commend his intonation as he says, "Chief Minister must resign!" And we can continue to wade towards those marooned in their huts.

We're always asked if we're from Sun TV. Or Jaya TV. Some ask if we are Karunandhi. Or Jayalalitha. When we tell them it's an English news channel, the crowd disperses. Some inform the disinterested that "nowadays you can talk in Tamil for English channels also."

Some women, usually the first ones to speak, shuffle towards me. Many that talk to the mike know what the media likes. They've seen too many cameras, answered the same questions a trillion times, and seen nothing happen despite all that. They've also seen people's heart going out to the woman beating her chest in Nagapattinam. They saw the channel proudly showing off the impact of that footage. They know she received Rs. 6 lakh.

These women start from the beginning, tell me where the government machinery failed, where they themselves were at fault, what they need, and how sure they are not much help will come their way. The greater the pain, the more difficult it is to speak. Especially to someone holding a mike. Sometimes a tear or two wets the cheek. As if only someone's tears can tell us how unpredictably cruel life can be. I never know what to say, so just look on.

But, that day, when she cried that her daughter was washed away in the flood, the others behind her were smiling. They wanted her to talk to me, and cry, if she wanted, but they knew, just as well as I did, that she was lying. She had no daughter. I knew I wasn’t going to show this on TV, but none of us were angry about her lie. She'd been through agony, even if it wasn't because her baby died. Her only house broke, all her belongings were too soggy to be of any use ever and she was stuck with the loans she took to buy them, her husband couldn't go fishing, and she had no fish to sell. They had no water to drink, or food to eat for a month. Only cameras to talk to once in a while. Her daughter didn't have to die for her to cry. She thinks maybe more people are listening because she's crying.

Of course, everyone can see the drama in it all. Dripping with a stage-set sort of feeling. I will not carry her tears on TV just so people can ignore her other real agonies.

My only hope was the children. I remember being told they can never lie. When I ask a 7-year-old what happened to his sister who was born a few months ago, he looks me straight in the eye and says his father boiled her in the cauldron. But to the mike, he says she's growing up in grandma's house in the city.

I look for someone else who'll talk to the mike. Maybe they too will embellish the truth, or paint it in peaceful colours.

The eyes. We've just got to look at the eyes to know.